Something I've found while researching

The Stowaway is a vast and (to me, at least) surprising discrepancy in the prices of out-of-print books. Some academic volumes from the ancient days of the 1980s are so expensive I can't justify buying one for a single essay on Peter Pan. But in a much happier turn of events, books from the turn of the 19th century are often ridiculously affordable. They're sold as "used," not quite antiques, not quite archivable. And while they're not as cheap as a used Grisham novel, they're also not the price you might expect for tangible bits of history.

I continue to take advantage of the situation.

The most expensive of the books above, Volume I of

The Novels, Tales and Sketches of J. M. Barrie, was $10. The others were half that or less. (Ironically, I can't read them now because I have begun channel Barrie's writing style with almost no provocation, and it begins to seep into

The Stowaway, where it doesn't belong.)

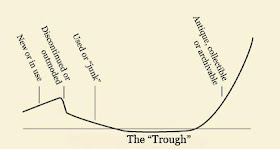

I can only conclude these books have fallen into "the Trough of No Value." Mike Johnston of

The Online Photographerr has this graph in his

essay on the subject:

Johnston's examples include photographic negatives, computers, and lunchboxes from the 1950s and 1960s. "One of the problems of historical preservation is that people only tend to preserve things that are valuable," he writes. "And the problem with that is that value fluctuates over time." This, of course, is difficult to predict.

He also mentions that the craftsmanship of an item can determine its fall into the Trough. And this applies to books as well, of course. A perfectly-preserved first edition of a still-popular book may cost hundreds or thousands of dollars--why I don't yet have my own first edition of

Peter and Wendy. But if someone like me wants a book mainly for its contents, it's worth keeping track of the Trough.

Luckily for my own collecting, I often appreciate a book all the more if it shows signs of its lifespan and evidence that it was loved. A "Merry Christmas" message from Aunt Lizzie, 1909, has value to me which it might not to a regular book collector. (This is the same impulse that has prevented me from refinishing the table I used as the background for these book photographs. A practical nostalgia?)

If you're willing to overlook some damage and signs of age, you can find a treasure trove of books from the Edwardian era. They may be offered by some unexpected sources, and that's part of the fun. I paid under $20.00 for most of these, some of which I discovered in used or antique book stores, others which I found on eBay or from

ABE Books. If they were first editions, or in better condition, they would of course be priced higher, although I think most of them would still qualify as "affordable." But I find value in their shabbiness, in evidence they were read and maybe even loved.

|

| My copy of the 1907 The Girl's Own Annual |

So if you're interested in books of a hundred years ago, this is a good time to buy them. There's no guarantee they'll go up in price, of course, and we can't predict the desires and contexts of future societies. But from what I've observed, and from what the Trough of No Value tells us, these affordable books aren't likely to stay that way forever.

|

| "I must go down to the sea again" |

|

| Not Peter Pan, but relevant to The Stowaway |

These books come to us without commentary, giving us a direct look into history without the overlay of our present priorities. And of course reading books from another era is one of the best ways to learn the diction and styles of writing from the past--very useful when writing about those times. But that's a subject for another day.