"Christina's World" is certainly Andrew Wyeth's most famous painting (although it was not at the SAM exhibit--it lives at MOMA in New York and does not travel). The history of the land around him--his home in Chadd's Ford, Pennsylvania, and a summer home in Maine--permeates all of Wyeth's work, and that leads us forthwith to his connection with fictional pirates.

|

| Captain Keitt by Howard Pyle (1907) |

I've written before in this blog about Howard Pyle, the illustrator who brought the image of the quintessential swashbuckling pirate to the modern world.

One of Pyle's students in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, was N. C. (Newell Convers) Wyeth, Andrew's father. N. C. Wyeth illustrated 112 books during his lifetime, including a 1911 edition of Treasure Island which is considered a masterpiece.

|

| "Trodden Weed," 1951 |

Wyeth painted this self-portrait of sorts, Trodden Weed, with a piratical pair of boots previously owned by Howard Pyle.

|

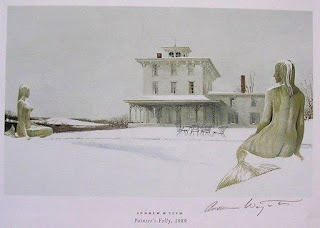

| Painter's Folly (1989). The house went up for sale in 2014 and was ultimately bought by the township of Chadd's Ford in 2017. Note the mermaids! |

Andrew Wyeth considered Pyle his "spiritual grandfather," said Joyce Hill Stoner, the art conservator who worked for the Wyeths for thirty years. Pyle's house, Painter's Folly was the subject of several of Wyeth's paintings, as were Helen and George Sipala, the couple who lived in the house during his lifetime.

Perhaps it is odd that I was so alert to connections to Peter Pan, but note the hook appendage in this portrait of Wyeth's neighbor Bill Hoper, a blacksmith and handyman. The docent who discussed the exhibit at SAM said that Wyeth's father wouldn't have approved of so much reality in a portrait--not an issue for Andrew.

Although he was one of the foremost American artists of the twentieth century, his style of work became unfashionable during his lifetime, considered too sentimental by those who preferred their art abstract. I admit I was drawn to seeing this exhibit because a friend of mine described it as bleak, and I hoped I would find some comfort in that given my own mindset after the death of my father last September. What I found in Andrew Wyeth's paintings was imagery that is almost surreal, realism that expands into symbol and emotion, a depth beneath what has been dismissed as cartoonish or antiquated. This is what I hope in some small way to bring to my portrayal of Captain James Hook: something close to the heart, or maybe the bone.

“Life is strange,” Wyeth once told [Edgar Allen Beem]. “From the outside, things may look one way, but when you look inside, they’re very different.”

* * *

Note for further reading: I came across A Piece of the World, a fictionalized memoir of Christina Olson of "Christina's World," not long after seeing the Winter is Always exhibit. Naturally, it is now on my reading list.